On our quest to replace Sidekiq with RabbitMQ we already know how to enqueue messages based on various criteria, and already can massively flood our little Rails app with messages. There remain some problems, though: We haven't handled what happens if the broker crashes and takes the content of queues with him, or more complex scenarios where messages consisting of plain strings or routing keys with wildcards aren't enough to satisfy our needs. Also, in our previous scenarios all messages were processed immediately, what is not exactly what background jobs are made for.

A first look at worker queues

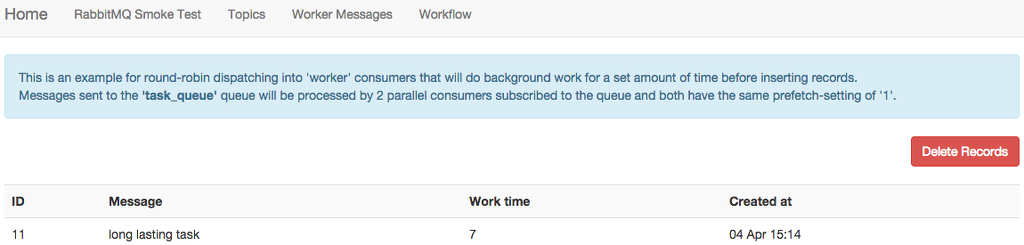

Imagine you would want to defer long lasting jobs to background workers. They are put in a queue, are fetched from it when it's teir turn, they run for some time and eventually return some sort of result, may it be a generated file or the result of some expensive computing task. To simulate this behaviour, the two sample programs will do the following: The message is sent from the Java application including the instruction how long the task should take being processed in the Rails application. This is solely for demonstration purposes, in a real world scenario you would have no idea how long the work will take, this is why you use background workers in the first place. Again, the Rails app will do nothing more but insert the incoming message into the database, including the passed on duration. The applications present themselves like this:

Making the Rails application wait for some time is a no-brainer, we'll just use the classic Kernel#sleep method. But how to control how long it should sleep? From what we know up until now, we could transmit the duration as part of the message body itself, and then somehow parse the incoming message body string. This is kinda cumbersome, and RabbitMQ provides a much better way to send arbitrary data along with the message.

Message properties

The basicPublish method we were using beforehand had one ununsed argument... until now:

channel.basicPublish("", queueName, null, message.getBytes());

Instead of null, we could have sent an AMQP.BasicProperties object (in Java land), in Ruby it's just a Hash-like object. To be honest: We did this implicitly all along. If you look at the three block arguments for processing messages: |delivery_info, properties, body| you'll notice the delivery_info and properties arguments. The Bunny documentation about messages includes detailed lists what information and properties are implicitly submitted. For example, some data (including the routing key) is always accessible (for example via delivery_info.routing_key), other arbitrary properties can just be defined as a Hash (or whatever your programming language API arrogates) in the 'headers' property.

What's really interesting here is that you can use the properties in any way you want. RabbitMQ even builds concepts like RPC around those properties (for example, RPC uses the correlation_id-, message_id- and reply_to-properties, but RPC won't be covered here). To get our little worker scenario running, we could have put the extra 'duration' parameter in the 'headers' property, which is just a Hash with user-defined keys. Or we could use one of the already defined properties (a.k.a 'well-known properties'). I decided to use the type property. There are no constraints on how to use any property for anything, so in my case I just want it to hold the string containing the entered duration from aboe shown Java GUI. Here it is, the new basicPublish method to send a message to the worker queue:

// Insert workTime-info as message "type" property.

// deliveryMode(2) = persistent

// (java.lang.String exchange, java.lang.String routingKey,

// AMQP.BasicProperties props, byte[] body)

channel.basicPublish("", "task_queue",

new AMQP.BasicProperties.Builder()

.contentType("text/plain").deliveryMode(2)

.type(workTime)

.build(),

message.getBytes());

In Java, you use the AMQPBasicProperties.Builder class to return a configured object. We'll publish the message directly using the direct exchange 'task_queue', which will just insert it into the queue of the same name.

Looking at above code, you'll notice that there is one other property defined: deliveryMode(2), and as the comment reveals it, it tells the message to be persistent. This is the next topic we'll have to tackle, so let's continue with durability.

RabbitMQ and durability

RabbitMQ can cover just about any messaging scenario. But in our case, fire-and-forget-messages are not excatly what we want. We want to be able to persist and re-enqueue messages if something goes wrong, and we don't want to declare anonymous, short-lived queues. For that reason we'll streamline the configuration in our little programs. In config/unicorn.rb we declare the two queues for worker messages like this:

worker_queue_1 = rabbitmq_channel.queue("task_queue", durable: true)

rabbitmq_channel.prefetch(1)

worker_queue_1.subscribe(manual_ack: true) do |info, prop, body|

# simulate work with data from 'type' property (number string)

sleep prop.type.to_i

WorkerReceiver.new(info, prop, body)

rabbitmq_channel.ack(info.delivery_tag)

end

We give the queue the name 'task_queue' and set its durability to true. This sets the queue lifespan not to be dependent on consumers subscribed to it, the queue will survive a broker restart and it will be shareable by many consumers - exactly the behaviour we want. Together with the 'persistent' flag on the message we get a queue which won't loose anything, even after the message broker has to restart. As in the first few examples in this blog post series, we use the implicit consumer given by the subscribe method, and as always actually saving records is delegated to a service-like (FooReceiver) object. You can also see how easy we can access the type property of the message which is set by the Java GUI. But what exactly are those ack-thingies appearing all over the place?

Message acknowledgement

We know how to persist messages and queues, so far so good. But how exactly does the broker decide when it's time to remove messages from the queue? In other words, how does the message broker know when a message's processing is "finished" and it can be safely removed from the queue? This is of utmost importance, especially if we want to deal with long-running background tasks. But not to worry, RabbitMQ got you covered. In above code, you'll see that the subscribe method does get a new parameter (manual_ack set to true) and again a method named ack is called in the block processing the message, right after the simulated long work is done. The manual_ack parameter simply instructs the consumer to insist of a message to be acknowledged. In a multi-consumer scenario, this would mean if the first consumer fails processing the message, the broker would deliver it to another consumer until it's acknowledged. This is exactly what we want. The Rails application defines two consumers for the 'task_queue', and if one consumer is busy working on a longer-lasting job it will automatically redirect it to the other consumer. Together with the configured durablity settings above, undeliverable messages won't be lost, since the broker will leave messages in the queue until at least one consumer is subscribed to the queue and is free to process messages. The second call to ack(info.delivery_tag) eventually tells the channel to acknowledge the message using it's delivery_tag property from the implicit delivery_info metadata. As explained in the documentation, it's implemented as a channel-specific increasing number, you shouldn't have to deal with it manually.

The functionality to signal the broker that messages have failed (via the reject method) won't be covered here, since we would have to implement all the logic to handle failed messages and re-enqueuing them ourselves. The next blog post will show a much nicer way for this - just be patient.

There is one piece of information missing - how does the broker deal with occupied consumers?

Message prefetching

As you may have noticed on the screenshots and in the code above, there are some hints about round-robin and the prefetch(1) setting. What do they mean?

If you try out the Java and Rails applications, you can easily provoke a situation like this: You insert a long-lasting message into the 'task_queue', and immediately after that some not-too-long-lasting messages. Of course the broker, sice the longer-lasting message came in first, will order the next free consumer to grab the next message, and again and again until the first broker has sent his acknowledgement and is available again to consume messages.

And that's what the prefetch-setting is for: You can manipulate the amount of messages each consumer will grab from the queue. It's a simple way to do load-balancing, so to speak. It's a channel-wide setting and only active for consumers which have manual_ack set to true.

We've covered a whole lot. You should have a good grasp by now on how the several parts of RabbitMQ work together. The last part of this blog post series will be about one more abstraction layer above RabbitMQ and Bunny and how to get workflows and automatic re-enqueuing running.