If you followed my advice in the last blog post and had a look at the exchanges in the management UI, you were able to see that there are already some other exchanges present, like 'amqp.topic', 'amqp.fanout', 'amqp.headers' and so on. What exactly are they?

Not the whole truth

What information I held back up to this point is that there are several types of exchanges, and each type can be used to implement different message delivery behaviour. In the previous examples messages would be delivered to exactly one queue (the one named like the given routing key), and all other messages wouldn't be processed. But RabbitMQ can be used to implement arbitrary routing patterns, including dispatching copies of a message to many or all subscribed queues, exclusive routing where only one queue is getting a specific message and anything else in between by using topic exchanges. Or you can omit the routing key altogether and control routing by more complex constructs like hashes. Let's have a look at the four types of exchanges.

Exchange types

- Direct exchange That's the type we were using all along. They deliver a message to a queue if the routing key of the message matches the routing key of the bound queue.

- Topic exchange Topic exchanges route messages to one or many different queues based on a pattern given by the routing key.

- Headers exchange They route messages not by the routing key, but by metadata definded in the message's header segment. They are used when strings as routing keys are not sufficient to express the rules you want to route by.

- Fanout exchange Fanouts are pretty simple. They just deliver a copy of a message to all bound queues and ignore the routing key. We won't cover them here any further.

As illustrated in the Bunny docs, exchanges can be declared either by instantiating a new Exchange object or by calling the #direct, #topic etc. methods on a Channel object. Once again, the Bunny API is rather terse.

Now that we know a little bit more about exchanges and messages, let's look at some examples for queues that get messages delivered by a little bit more complex rules.

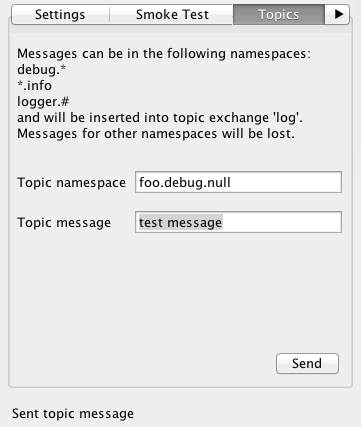

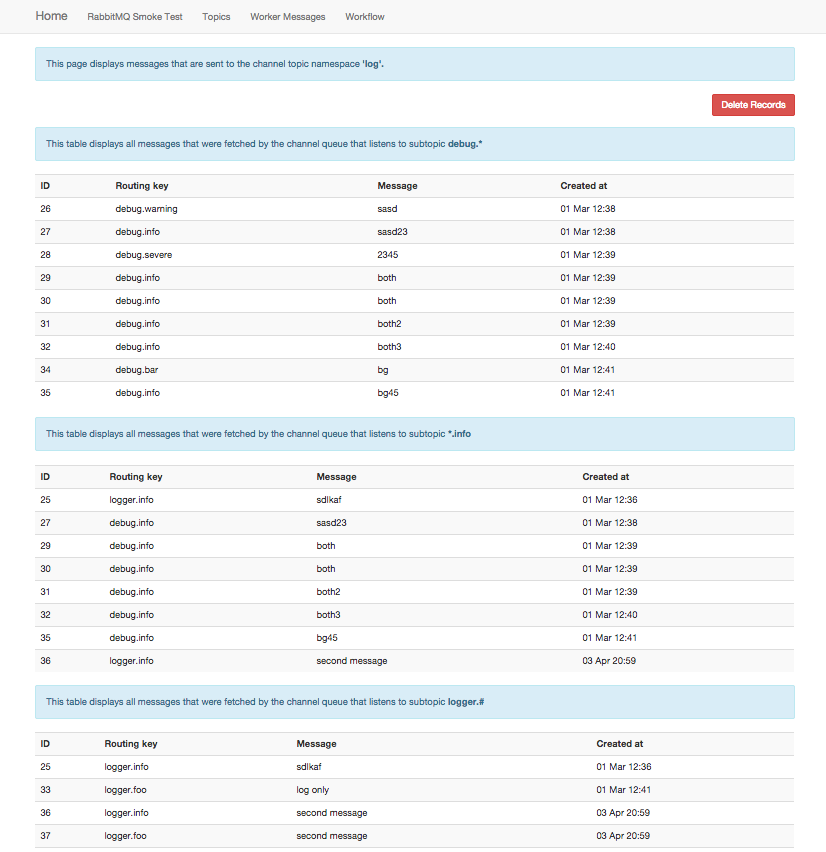

Topics in the sample apps

Here is what we want to accomplish: We want to implement a simple "logging" scenario, in which messages bear three different severity levels. Our application should receive those messages and persist them accordingly. As in real life, severity levels are defined as subsets, the higher or lower you set your level, the more or less messages you will see. Translated into RabbitMQ semantics, you work with wildcard segments in routing key strings. The available wildcards are "*" and "#". The asterisk means "exactly one", and the pound sign means "zero or more". For example:

debug.*

will receive messages with routing key

debug.something

but not

debug

debug.something.more

*.info

will receive messages with routing key

foo.info

but not

info

foo.bar.info

and finally

logger.#

will receive messages with routing keys

logger

logger.something

As you can see, implementing the behaviour of having two queues sharing the same keys using wildcards is quite simple. In above example, if you send a message with the key logger.info two queues will receive the message. Using those rules you could implement different severity levels like this: "I want to have 'debug' messages separated from the others, but be able to deliver 'info' and 'standard' logger messages at once or seperated, too". And this is exactly what the sample Java and Rails applications do:

And here is how they are implemented:

Explicit consumer classes

In the config/unicorn.rb file we configure more Bunny connections, again each in its own Thread block. Instead of using the nameless exchange we declare one "topic" exchange and three queues, one for each of the routing keys above:

rabbitmq_channel = rabbitmq_connection.create_channel

topic = rabbitmq_channel.topic("log") # returns exchange of type topic named "log"

info_queue = rabbitmq_channel.queue("info") # declare queue named "info"

info_queue.bind(topic, routing_key: "*.info") # bind the queue to the topic exchange

For demonstration puroposes and to make things more explicit, this time the queues subscribe with an explicit consumer:

info_consumer = TopicConsumer.new(rabbitmq_channel, info_queue)

info_consumer.on_delivery() do |delivery_info, properties, body|

TopicReceiver.new(delivery_info.routing_key, body)

end

info_queue.subscribe_with(info_consumer)

This time the message properties are handled inside the block of the on_delivery method. The block parameters and message handling capabilities are the same as inside the block of the Queue#subscribe method (see last blog post). Note that instead of subscribe subscribe_with(consumer) is called.

The docs on consumer classes are pretty straightforward, and I'm only scratching the surface here of what's possible.

Sending topic messages

Once again, the Java code in the sample application has to do the same things as the Ruby code above: Declare an exchange named "log" of type "topic" on a channel object:

// (java.lang.String exchange, java.lang.String type)

channel.exchangeDeclare("log", "topic");

The way messages are sent is the same as usual, we just use the trustful basicPublish() method and publish into the "log" exchange with the entered routing key from the Java GUI.

Now that we have a very configurable way to control how messages will be forwareded to queues, we can look at the next feature we'll cover: Basic worker queues.